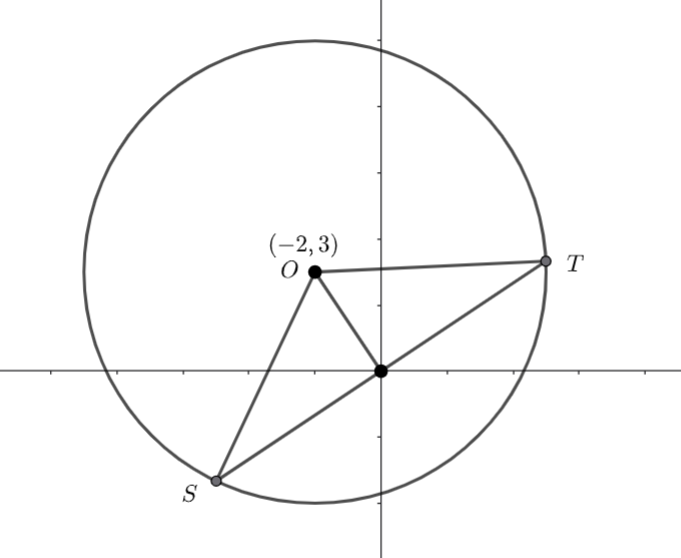

In the diagram below, ![]() and

and ![]() lie on the circle with centre

lie on the circle with centre ![]() . If

. If ![]() and

and ![]() , determine with reasoning

, determine with reasoning ![]() and

and ![]()

We know ![]() – radii of the circle.

– radii of the circle.

Which means, ![]() is isosceles and

is isosceles and ![]() – equal angles isosceles triangle.

– equal angles isosceles triangle.

![]() – angle at the centre twice the angle at the circumference.

– angle at the centre twice the angle at the circumference.

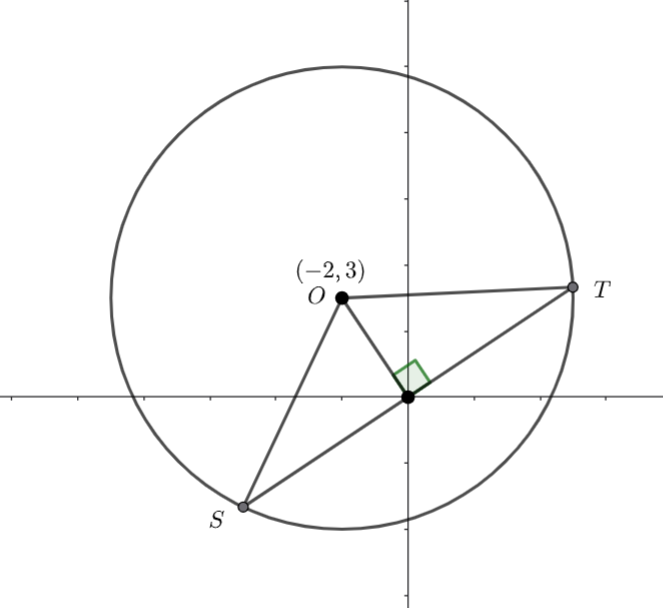

![]()

This means ![]() – angles on a straight line are supplementary

– angles on a straight line are supplementary

![]() – equal angles isosceles triangle and the angle sum of a triangle.

– equal angles isosceles triangle and the angle sum of a triangle.

![]() – angle at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

– angle at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

![]() – angles at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

– angles at the circumference subtended by the same arc are congruent.

![]() – equal angle isosceles triangle

– equal angle isosceles triangle

Hence ![]()

line)

line)